Nearly 70 years since Bond’s birth, Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang and his creator still lure us into heedless adventure

This essay contains content expanded from the Weekly Wag

James Bond, a most durable secret agent, was born out of the crisis of a twentieth century man. In 1952, Ian Lancaster Fleming was 43, and, up until that point, a notorious bachelor. But in midlife, he suddenly found himself engaged to his most consistent lover, Ann Charteris, Lady O’Neill and Viscountess Rothermere, who was pregnant with their child. Theirs was not a conventional relationship of that era, or this one, but circumstance placed the pair in a bourgeois box.

“I was on the edge of getting married, and I was frenzied at the prospect of this great step in my life,” the author said in a 1963 appearance on the venerable BBC Radio program Desert Island Discs. “I really wanted to take my mind off the agony, so I decided to sit down and write a book.”

It’s a very Ian Fleming sort of story, in which the birth of a billion dollar pop culture juggernaut is played off as rogue’s luck. There’s a hint of the author’s much-discussed misogyny in the yarn, but more importantly, it reveals what he understood better than most anybody—the craving of human beings to escape the grind of modern life. Fleming is one of the more chronicled and analyzed writers of the postwar period, but he had a habit of publicly downplaying his work as a bit of a lark. That larkiness was a tic of his generation and class, a mask for those who had experienced horror on previously unimagined scale. It tended to glaze over snobbery (and worse) with a veneer of charm. Then again, charm got Ian Fleming a considerable distance. He made an art of never taking himself or his golden goose seriously. “I’m not in the Shakespeare stakes,” he said. “I’ve got no ambitions.”

Sixty-eight years and many cultural shifts after the publication of the first 007 novel, Casino Royale, that coy assessment begs reëvaluation. Fleming died of a heart attack at 56 in 1964, before the premiere of the third Bond movie, Goldfinger. His character— memorably shorthanded as Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang—carried on quite lucratively without him. Despite being delayed three times by the Covid-19 pandemic, No Time to Die, the 25th film in the official 007 series, opened in theaters Oct. 8, raking in $56 million in its opening weekend (the film has already made more than $300 million internationally). In six decades, the franchise has earned more than $5 billion and starred six different actors in the title role, most recently Daniel Craig, whose planned departure after Die has sparked intense speculation about his replacement. In any incarnation, James Bond is that rarest of creatures: The hero who can still reliably open a movie. The lure of that I.P. figured in Amazon’s recent acquisition of MGM for more than $8 billion. That deal keeps the descendants of mogul Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli, whose EON Productions controls Bond’s movie career, firmly in command of his cinematic future. Broccoli’s daughter Barbara has made it clear there won’t be a flood of spinoffs streaming in your living room anytime soon. The goal, at this early date, is to protect 007 as theatrical spectacle.

As a publishing icon, Bond also thrives. Fleming banged out 12 Bond novels and two short story collections on his famous gold typewriter during annual sojourns at Goldeneye, his Jamaican retreat. That discipline—2,000 words a day, one book a year, a body of work in little more than a decade—was part of self-consciously conjured myth. The high-living, wildly popular paperback writer was also a serious one, as his 1963 essay, How to Write a Thriller, makes clear:

While thrillers may not be Literature with a capital L, it is possible to write what I can best describe as “Thrillers designed to be read as literature,” the practitioners of which have included such as Edgar Allan Poe, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Eric Ambler and Graham Greene. I see nothing shameful in aiming as high as these.

None of those esteemed writers inhabit the same stratosphere. Since Fleming’s death, 007 has had further adventures in officially sanctioned books by multiple authors, among them Kingsley Amis, John Gardner, and William Boyd. There is a Young Bond offshoot, graphic novels, even a series called The Moneypenny Diaries.

Then there are Bond’s powers as an agent with a license to shill. Fleming peppered his novels with references to Moreland cigarettes, Gordon’s Gin, Rolex (the Oyster Perpetual watch), Bentley automobiles, and even Tiptree “Little Scarlet” Strawberry Jam. That tradition continues on a massive scale. Online, one can purchase “Double-O” socks ($18.95), a SPECTRE symbol wine stopper ($31.95), and a Bond calf leather carryall by Michael Kors Collection ($2,350), from an authorized 007 store. Tom Ford (which replaced Turnbull & Asser as Bond’s shirtmaker), Omega (sales of its Seamaster watch increased by 20 percent after Daniel Craig wore one in the 2006 film of Casino Royale), BWW, Heineken, Triumph Motorcycles and Adidas are all in bed with the super spy. For its latest release, MGM partnered with VeVe, a crypto currency company, to issue limited edition James Bond NFT’s.

Official business doesn’t come close to capturing the character’s cultural footprint. Bond has spawned thousands of imitators across platforms, endless spoofs and even a music genre (sung by Shirley Bassey or Billie Eilish, the swoony horns and grandiose orchestration of a John Barry-influenced Bond theme are unmistakable). Without Fleming’s character, conceptions of modern espionage, the image of Britain—Queen Elizabeth II appeared to parachute into London’s Olympic stadium with 007 to mark the opening of the 2012 Games—and our knotty gender politics would all be rather different. With respect to the Shakespeare stakes, it’s clear which writer has more contemporary global influence.

Among authors, Fleming’s real rival is Agatha Christie, the world’s bestselling novelist, but Christie wrote 72 novels, more than 150 short stories, and numerous plays over the span of her 85 years (curiously, she named a character James Bond before Fleming did, in a 1926 short story called The Rajah’s Emerald) . Fleming was hardly so prolific; his lasting literary contribution outside the Bond canon is Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, published posthumously in 1964. Yet, like Christie (and Rowling, Lucas and Disney) he was able to create a universe, populated by a memorable supporting cast (M., Q., Moneypenny), villains (Blofeld, Oddjob, Scaramanga), and of course, heroines (Vesper Lynd, Pussy Galore, Honey Ryder), all of whom reveal Fleming’s sexual blind spots and proclivities. Fleming understood publicity, and he shamelessly borrowed character details from the real-life girlfriends, school bullies, chums, and obnoxious neighbors who populated a very interesting life.

Most remarkably, there is his contribution to English itself. Bondspeak — Live and Let Die, The World is Not Enough, Octopussy—is a language all its own, punchy, evocative, silly-sexy, cynical, indelible. This is the hard, manipulative argot of advertising, or in today’s terms, branding. Fleming understood our obsession with tech, kinky sex, ultra-violence, and consumption itself. That supercharged fetish for brand names is echoed in Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, in hip hop, and in all manner of testosterone-driven pop fantasies. Fleming simply got there first.

That a contemporary of Noël Coward and Evelyn Waugh should remain highly commercial when many of his peers were long ago banished to the dustier of nooks of college libraries is a curiosity. Fleming may have been a modern writer, but he was, in some unflattering ways, an old fashioned person. His attitudes about race, sex, and class were retrograde by the 1950s. The anti-Bond line—Fleming’s villains are suspiciously foreign, physically deformed, racially mixed, or vaguely Jewish; the treatment of women (whom the author once compared to pets) and homosexuality is abysmal; the informing attitudes colonialist—is as venerable as the character. The critic Paul Johnson famously summed up those failings in a 1958 New Statesman review of Dr. No, which he derided as having “three basic ingredients…all unhealthy, all thoroughly English: the sadism of a schoolboy bully, the mechanical, two-dimensional sex-longings of a frustrated adolescent, and the crude, snob-cravings of a suburban adult.”

Johnson’s indictment of Fleming’s Sex, Snobbery and Sadism endures. Still, Bond has dodged cancellation as easily as Goldfinger’s emasculating laser beam. However moderated recent Bond movies are by multiculturalism, feminism, and a more enlightened globalism, whether or not the new 007 is portrayed by a person of color, or becomes female, the character moves audiences on a more reptilian level—the magical, border-crossing lure of brand, brand, kiss, kiss, bang, bang. This appeal has transcended the Cold War politics of Fleming’s day, for 007 is likely even more popular in the countries of the developing world and former Communist bloc than he is in his homeland.

This is a credit to Fleming’s knack for fantasy, and his timing. Bond was invented just as the postwar West experienced an unprecedented surge in affluence, traditional conventions about premarital sex were being tossed aside, and jet travel became a reality for millions in an expanding middle class. To read a 007 paperback on vacation in one of the many locales Fleming depicted in his novels — Nassau, the Swiss Alps, Geneva, Las Vegas—was no longer a luxury beyond the reach of all but the very rich. To imagine that sexual pleasure could come without strings became possible with the Pill. Yet Fleming was an odd ambassador for this liberated world, because he was both personally libertine and instinctively reactionary.

Fleming was born into privilege in 1908, the son of Evelyn Ste. Croix Rose, a famed society beauty, and Valentine Fleming, a Scottish Tory MP killed in World War I. Biographers have explored how the loss of a father when Fleming was nine shaped him; the relationship of Bond to his spymaster M arguably gives voice to both Fleming’s yearning for a paternal figure and reflects his difficulties with a formidable mother. A middle child in a family of four boys, he was a fantasist from an early age, particularly drawn to H.C. McNeile’s Bulldog Drummond stories and the adventure novels of John Buchan. He was in every way overshadowed by his eldest brother Peter, who became an explorer, celebrated WW II commando, travel writer, and one of the many models for 007 himself.

In contrast to Peter, young Ian was “a bit of a duffer,” as Bond expert Klaus Dodds put it in a May 13 BBC interview. Fleming followed his brother to Eton, where he was an undistinguished in everything but athletics and developed a reputation for wildness. (Like many Englishmen of his generation, floggings at boarding school may have also triggered an interest in sadomasochism.) Lack of success at Eton led the Flemings to pull Ian out a term early and send him to what was then called Sandhurst Military College. After he contracted gonorrhea from a prostitute, his military education was abruptly ended; Fleming finished his education in Switzerland. Gifted at languages, he applied to the Foreign Service but failed to score high enough on the placement exams; He then went to work for Reuters as a reporter and had a brief, disastrous turn as a stockbroker.

This slide was arrested by World War II, which gave Fleming a purpose and an outlet for his outsized imagination. In the language of his era, Fleming had a good war, colorful enough to merit a 2014 BBC dramatization. As a naval intelligence officer, he proposed fantastical operations, including hiding commandos under the Rock of Gibraltar as part of a plan called Goldeneye, that came to nothing. At least one idea evolved into Operation MINCEMEAT, in which false information was planted on a corpse in the uniform of a naval officer and floated where it could be discovered by the Germans. More importantly, Fleming ingratiated himself to a powerful network of intelligence officers on both sides of the Atlantic. “Fleming is charming to be with, but would sell his own grandmother,” another intelligence officer told author and espionage expert Ben MacIntyre. “I like him a lot.”

The war brought Fleming to Jamaica, where he purchased the property in St. Mary Parish that became the Goldeneye compound (Fleming gave various inspirations for the name, including the Spanish operation and the Carson McCullers novel Reflections in a Golden Eye) . He returned to journalism, this time for the Sunday Times, and managed to negotiate a contract allowing him to spend three months a year in the Caribbean. His romantic adventurism continued. During the war, Fleming had had affairs with numerous women, including Muriel “Mu” Wright, often cited as the inspiration for doomed Bond heroines, the daughter of an MP and sometime model who was killed in a 1944 air raid. Prominent among his many other lovers was Ann Charteris, with whom Fleming had been involved since the 1930s. “He was enormously attractive, and had enormous charm,” she later said. Their extraordinary and difficult affair is captured in bracing correspondence. “I long for you even if you whip me, “ she wrote in a letter Fleming in the 1940s “I love being hurt by you and kissed afterwards.”

Whatever this frisson, Ann married the enormously wealthy financier Shane O’Neill, 3rd Baron O’Neill in 1932, and had two children with him before he was killed in action in 1944. A year after O’Neill’s death, she wed another paramour, Esmond Harmsworth, 2nd Viscount Rothermere, the owner of the Daily Mail. Her affair with Fleming continued through both marriages. Ann explained long absences in Jamaica to her second husband by saying she was visiting Noël Coward, Fleming’s neighbor.

1n 1948, Ann gave birth to a daughter by Fleming called Mary, who lived for eight hours. Her subsequent pregnancy precipitated a divorce from the then Lord Rothermere, from whom she was given a £100,000 settlement. She and Fleming finally wed on March 24, 1952; their son Caspar was born that August. By then, Fleming had embarked on his career as a novelist. An avid birdwatcher, he appropriated the name of his hero from the American author of the guidebook Birds of the West Indies. His career was aided by the couple’s wide net of very influential friends. In 1956, British Prime Minister Anthony Eden and his wife Clarissa spent a month at Goldeneye following the Suez Crisis; the visit boosted publicity for Fleming’s novel Diamonds are Forever, published that same year. Fleming’s most powerful fan in America was John F. Kennedy, who cited From Russia with Love a one of his favorite novels. The men met before Kennedy was elected President in 1960 and discussed Fidel Castro.

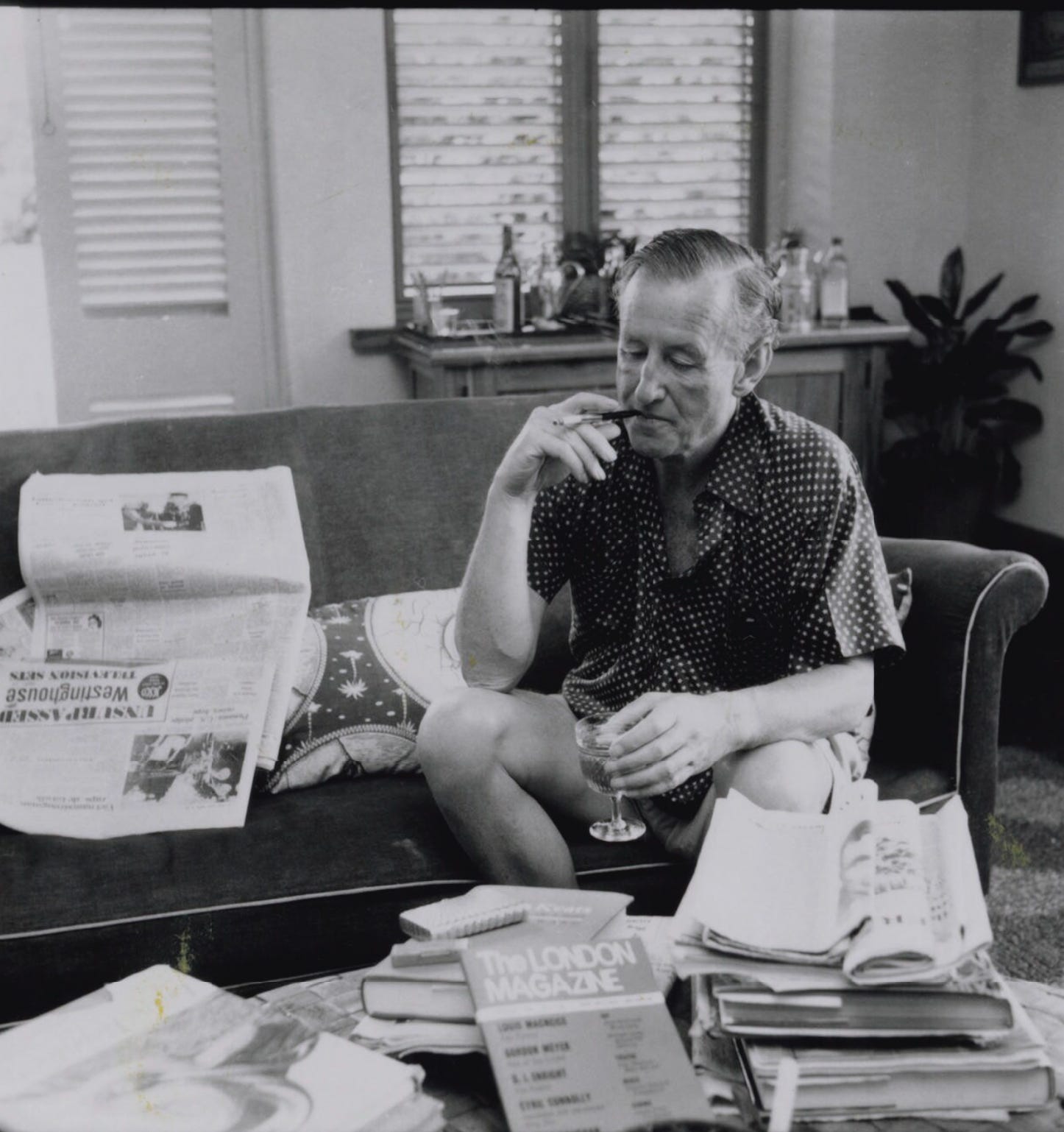

Bond’s popularity reached new heights in the Kennedy era, but both Fleming’s health and creativity were in decline. Hard drinking and 70 cigarette-a-day habit took their toll, and the relationship with Ann foundered. Both Flemings were unfaithful — Ian most notably with his neighbor, the Jamaican heiress Blanche Lindo Blackwell (another muse), and Ann with Hugh Gaitskell, leader of the Labour Party. “We are hurting each other to an extent that makes life hardly bearable,” he wrote to her.

As biographer Andrew Lycett notes, critical attacks on Fleming’s work increased in this period, and he was increasingly isolated in Goldeneye while his dazzling wife spent most of her time in London. After a 1961 heart attack, he continued to work—on books, scripts and even a promotional volume commissioned by the Kuwait Oil Company. Although still in his mid-fifties and a global celebrity, photos of the writer from the period show a man grown old before his time. In Fleming’s later novels, Bond is withering about the the softness of the postwar generation, who were easy pickings for Soviet manipulators. Only a remorseless blunt instrument like 007 stood between them and Communist subjugation.

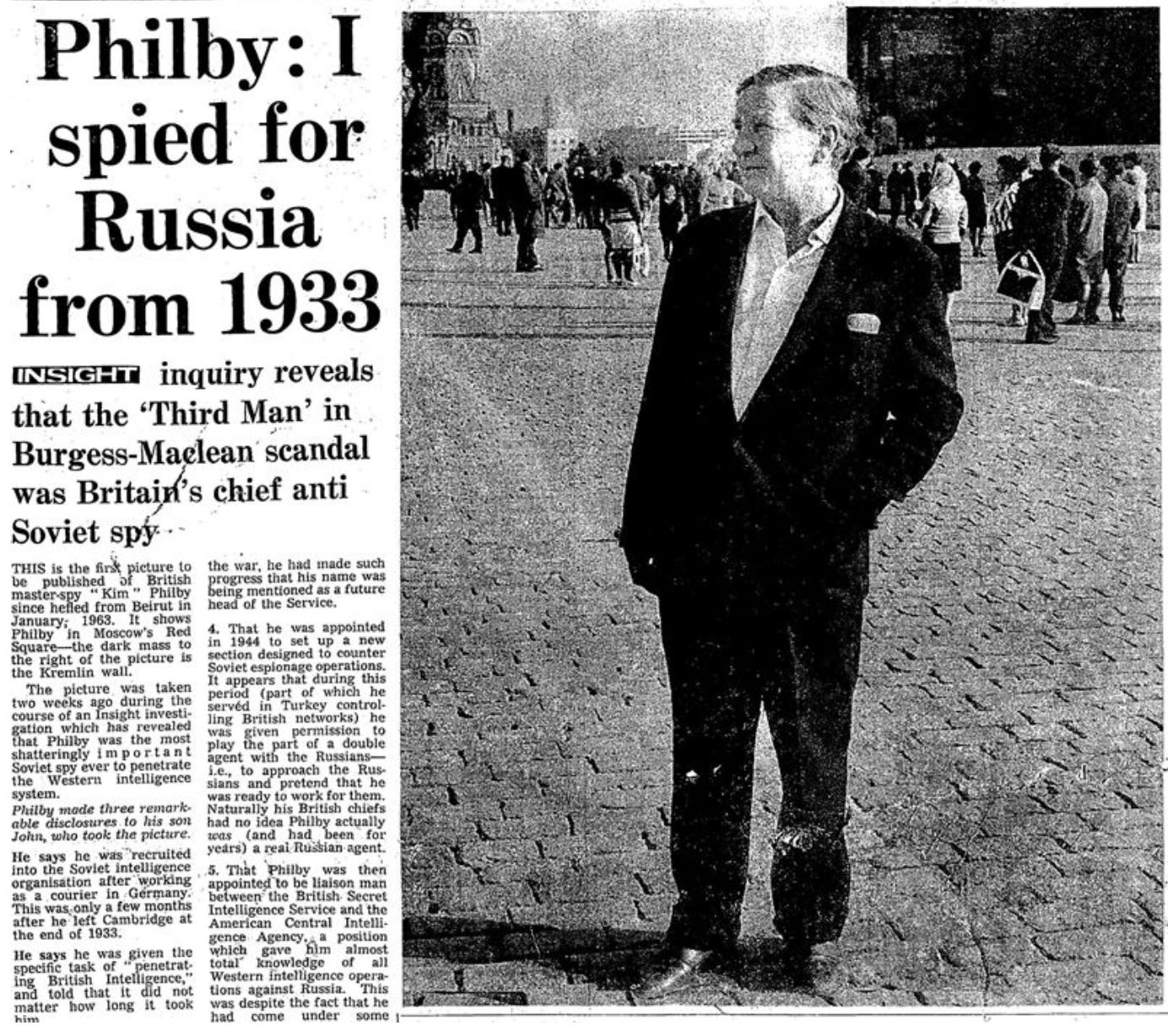

This was the greatest fantasy of all, for as Bond’s fame rose, real British power declined. Fleming began writing Casino Royale just as the full extent of Soviet infiltration within the British Secret Service was being uncovered. The exposure of Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Kim Philby and other members of their spy ring (like 007, Cambridge men all) humiliated British Intelligence and underscored the UK’s junior position in the transatlantic relationship. These were traitors of Fleming’s, education, erudition and class. The most formidable spies of the era, within both the CIA and the KGB, were colorless company men and apparatchiks. They were not charming, but the bureaucrats of John LeCarré’s Smiley’s People.

Fleming benefitted handsomely from the social transformations of the postwar era, but he remained firmly of the Establishment. His writing, in its name-checking and lecturing about the right way to make a martini, the right tie knot, the right shampoo—betrays the unease of an old guard at what’s coming next, when Eton and Oxbridge and membership in a club in St James’s won’t matter so terribly much anymore. “My dear girl, there are some things that just aren’t done, such as drinking Dom Perignon ’53 above the temperature of 38 degrees Fahrenheit,” Connery’s Bond says in the movie version of Goldfinger. “That’s as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs.” James Bond, once so lethal and swinging, is unmasked as a fussy square.

Presumably, Fleming would have approved of the scene, had he lived to see the movie. He collapsed after lunch with friends at the Royal St. George’s Gulf Club in Sandwich, Kent, and died in a nearby hospital on August 12, 1964, his son Caspar’s 12th birthday. Caspar Fleming, who might in a way be credited with spurring his father on to the project of a lifetime, died by suicide in 1975. He and his mother, Ann, who died in 1981, are buried with the author at a family plot in Sevenhampton, Wiltshire.

Fleming’s posthumous Bond books—The Man with the Golden Gun, Octopussy, and The Living Daylights—are generally considered lesser efforts. Post-Fleming, the Bond movies have borrowed the titles of these and other stories while straying wildly from their original plots. This has proven to be a smart strategy, for the modern world that Bond now inhabits bears increasingly little resemblance to the source material. The modern public, though, has never needed heroes—and the thrill that comes with momentary, exhilarating escape—more.

Beneath the hard candy surface, the baccarat, easy sex, casual brutality and fancy hotels, Bond remains an innocent, from a place where villains are vanquished and knights with codes of honor win the day. Fleming, like any arrested boy in confusing times, wanted nothing so much as a return to Neverland. His best quote about this ethos doesn’t come from any Bond novel, but Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, the book he wrote for his tragic son:

Never say ‘no’ to adventures, always say ‘yes,’ otherwise you’ll lead a very dull life.

After all our years with James Bond, there may be no clearer explanation of his eternal appeal—and of his maker’s enduring genius.

Sources and More on Fleming and Bond:

Ian Fleming, the Man Behind James Bond, by Andrew Lycett

The World is Not Enough; a biography of Ian Fleming by Oliver Buckton

Ian Fleming, a Personal Memoir by Robert Harling

Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory by Ben MacIntyre

The Letters of Ian Fleming to his wife Ann (née Charteris) “Darling Baby,” “Dear Monkey, Darling Pig, Etc.) Sothebys.

Extraordinary letters between Ian Fleming and Wife to be Sold by Mark Brown, The Guardian

For Sale: Trove of Tempestuous Letters Exchanged by Ian Fleming and His Wife, Ann. Brigit Katz, Smithsonian Magazine

Ian Fleming & The Birth of Bond, Dan Snow’s History Hit, May 13, 2021

Bond, the Secret Service & Exporting Britain’s Influence, Dan Snow’s History Hit, Sept. 29, 2021

Ian Fleming. Desert Island Discs: Fragment Archive, 1960-1969

IanFleming.Com, the website for the Ian Fleming Publications Ltd. and the Ian Fleming Estate