We’ve been powerfully distracted all these years. That has a cost.

This article contains expanded information from the Weekly Wag (it’s also a bit more than 240 characters).

The other day, I received a jolly message from Twitter congratulating me for having persisted on the platform for nine years, complete with illustrated balloons. This almost-decade has been momentous for Twitter, and decidedly more mixed for Me on Twitter. During this era, one of us upended modern discourse, while the other dipped in and out in a desultory way—making a wisecrack here, scurrying away in a panic there. One can point a finger at Twitter for all sorts of things, but it can’t take the rap for my failure to dominate its platform. It’s not that I don’t crave likes from millions, be they carbon-based or bots hatched in Vladivostok. It’s that building a robust audience requires strategic focus, which I do not have to the point of clinical diagnosis. More poignantly, it seems I require rapturous approval for everything I say. Social media has a cruel habit of reminding me of something I already know, which is that I am a person of relatively little importance.

There are still a few holdouts among us, avoiding social media (or at least lurking without posting), but that is not a viable option for those who are, however tenuously, in the media. As a blue check semi-professional, I’m fully aware of sundry hacks available to those who yearn to command phantom legions. One of the very best is to arrive on your chosen platform already famous. In lieu of that, you might try having a celebrity sit on your lap, or being a 16-year-old private school girl from Beverly Hills. Being on social media all the time is also very helpful. I’m not above pandering to potential followers in any number of ways, but in the process, I’ve discovered that is actually possible to feel one’s soul curdle. Many of us find self-promotion revolting, but the urge to try and scramble to the top of a digital bucket is incredibly powerful. It’s also widely represented as a smart career move and an awesome business model.

I’m being flip (a personality flaw), but I’m actually here to discuss something grave. Sloganeering aside, most of us aren’t on (insert platform name) for The Friends. We are there because it is where everybody else is, and it is important to know what they are saying, and in some instances, to get them to listen to us. About a generation in, we are still figuring out what that means for communication and society. Long before the internet, we were a culture that valued crowd validation above pretty much everything else. The ways in which our virtual ecosystem exacerbates this pathology are myriad. A majority of Americans, according to Pew, think social media is corrosive. That hardly means we are deleting our accounts. There was a time, long ago, when these platforms were adjacencies to IRL places, little clubby nooks for sounding off and sharing photos of sushi. Now, social media is simply The Media. (for about a billion Facebook users, it is also the entire internet). We are there, for the friends, and everything else, forever.

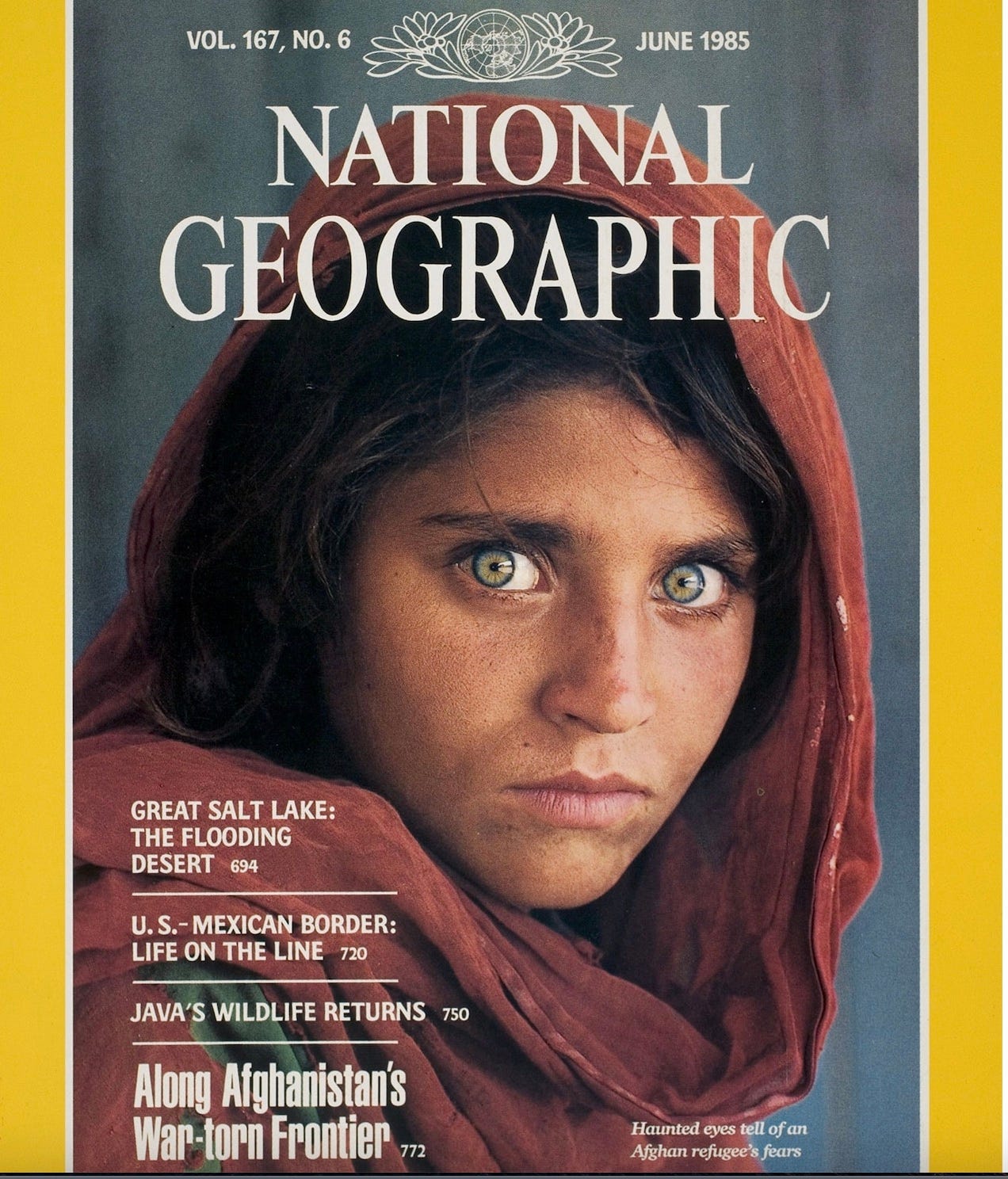

Why bring all this up, on my less-than-auspicious Twitterversary? (Hold onto the guardrails during the jarring pivot.) Because it coincides with one of those periodic intrusions of Big History into the social universe, which has the bracing effect of prying a few eyeballs away from FBoy Island and in this case, fixing them temporarily on Central Asia. This means that, in addition to reading stories about Afghanistan, you will soon read stories about how we experienced Afghanistan on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and even TikTok. For the keenly interested, at the very least, this is a social-first news experience, and hardly our maiden voyage in that regard.

By American standards, I know a little bit about Afghanistan, which means I know almost nothing about Afghanistan. The despair and outrage people feel when confronted with images coming out of Kabul is understandable. It is also confounding, because the train wreck was ongoing and hardly hidden from view. When things really hit the fan, our social platforms are good at hindsight, aggregation, blame, and galvanizing fellow travelers. Retroactively. Most of us didn’t pay attention to Afghanistan for 20 years because most of us simply preferred to look at—and be engaged by—other things.

Big Social loves metrics, so here are a few to gin you up: According to Politifact, nearly 250,000 human beings died in the American war in Afghanistan, among them, more than 6,000 American soldiers and contractors. More than 800,000 U.S. service members have served in Afghanistan since 2001, as well as thousands of allied coalition soldiers. The Defense Department says it spent about $2.6 trillion on a project any number of experts have described, at best, as misguided. Whatever else happens as the Taliban tries to solidify control over an ungovernable region, the death toll will mount. Mind-boggling numbers, surely. But let us consider that Justin Bieber reportedly has 455 million followers across his platforms. In the meaningful aggregate, the affluent, addled West has paid very little attention to Afghanistan at all.

Upgrade to paid

Apples and oranges, you may say (who knows how many of those Bielebers are bots). Yes, there have been reams of good journalism produced about Afghanistan, books written, movies made. Zero Dark Thirty won an Oscar in 2013, The Kite Runner was a bestseller, and Steve Coll was awarded a Pulitzer for Ghost Wars. There is a belated Amazon rush on related content. All of this seems ephemeral when compared to what truly preoccupied most of us in those two decades (BTS, Caitlyn Jenner, Trump, Grumpy Cat). After the longest conflict in our history, most Americans can’t name a single significant event of the war, reference a battle fought, or name any of its heroes or villains (beyond a few who worked in the Oval Office). Unless you are an Afghan, or part of the distressingly distinct subset we might call the soldier caste, you are unlikely to know someone who directly experienced the war. Yes, Afghanistan is trending. Now.

I’m not blaming social media platforms for pervasive ignorance. That is an enduring feature of the American experience. But the new media economy has played to our innate tendency to frontload idle diversion over harsh reality. It is a fairly accurate mirror of our supreme disinterest. Without the benefit of Wi-Fi, we are already inclined to opt out of difficult subjects and check into environments that confirm our beliefs. Little wonder that the architecture of our internets is an endless march of subdivisions where the like-minded shut themselves away together. The digital universe is an enormity beyond the fondest hopes of the twentieth century’s mass media builders, but it’s not mass in the old ways. It is an ever-mushrooming, fractious quilt of frequently gated constituencies. We all know new media algorithms are designed to feed us into ever-narrowing lanes of individual preference, and the lack of anything like a national hearth has obvious consequences when it comes to moments where we must reconcile ourselves to living in a democracy together.

I’m writing here of information not as a profit center or rage-juicer, but as a public trust, an antique novelty from the late twentieth century. The (good) ways in which the internet has liberated information are manifest. In the case of Afghanistan, there are many vivid communities obsessively focused on the war. There are many more that have debated our Central Asia policy through the lens of domestic politics. It was all there if you were inclined to go looking. Which, in bulk, (Y)ou were not. Affinity groups did not stitch themselves together into a broad public understanding of what has gone on in our name for many years. They have not led us to enlightenment or even basic fact knowledge about the history we are experiencing together.

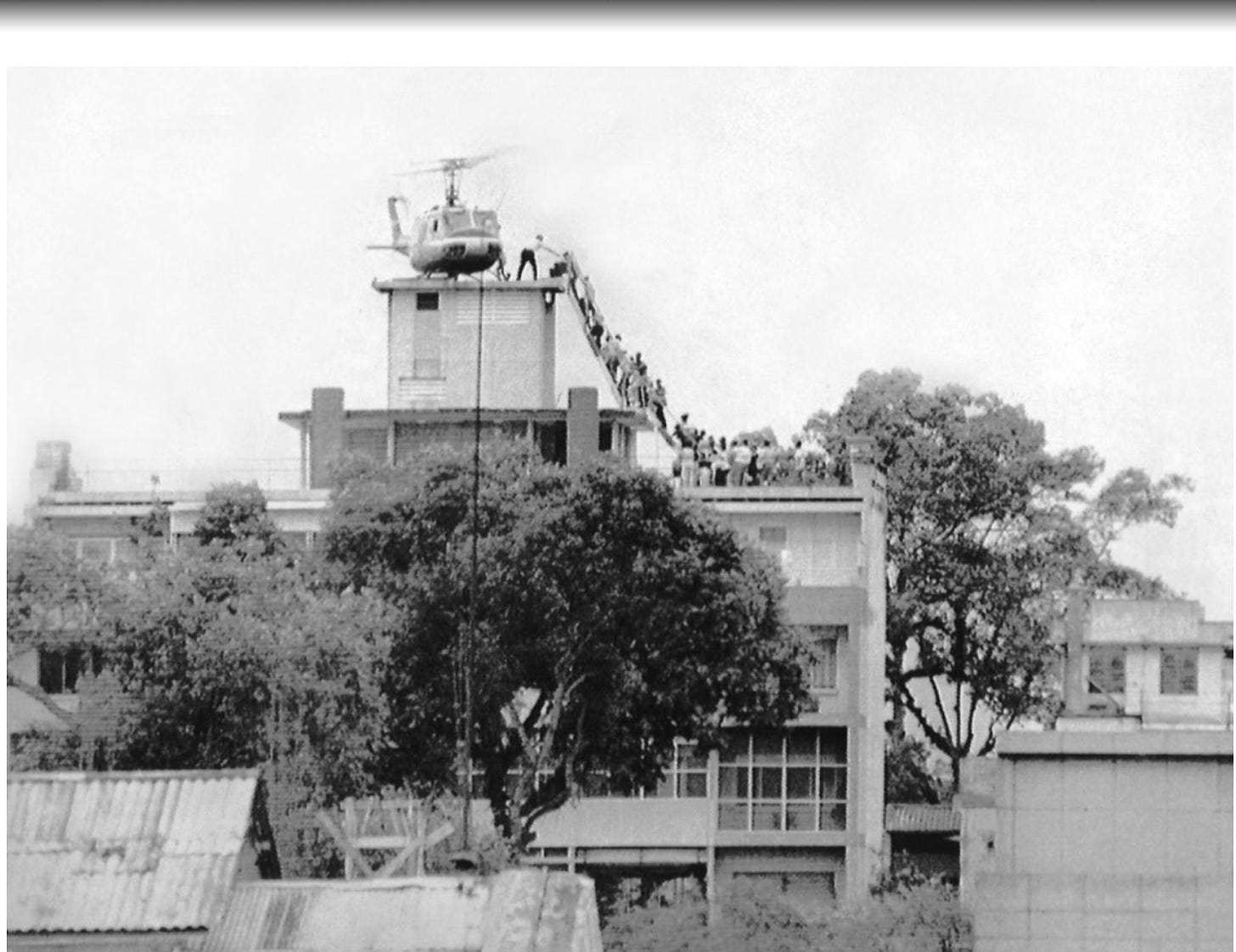

Most Westerners did not find Afghanistan on social media, or elsewhere. It found us, by crashing through our silos. When it did, we haplessly reached for comparisons — the most facile of which was Vietnam, that benchmark for all great American misadventures abroad. As thousands tried to escape the Taliban at Kabul’s airport, social media pulsed with comparisons to the fall of Saigon. My own reptilian brain pulled up an old image — that of a Huey evacuating Vietnamese refugees by Hubert Van Es— which I quickly found and lazily plopped into my feed.

Our media ecosystem is very hospitable to this sort of hot take, but whatever our ids and pundits tell us, Afghanistan is not Vietnam. For one thing, by 1975, everyday Americans had a much deeper understanding of Southeast Asia. There were but three major TV networks, watched by millions, covering the conflict. There were hundreds of rather lavishly staffed newspapers, wire services, and two major weekly news magazines doing the same. The country had been consumed for years by raging debate about the war, which permeated pop culture. A great many people far from the State Department knew about the Tet offensive and the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and despite government efforts to keep it hidden, they also learned of the bombing of Cambodia. There were plenty of idiotic distractions in that era, but for many reasons (a military draft being one) our midcentury information infrastructure did not let us off the hook.

Today we have an infinite variety of content producers, among them three major cable news networks with billions in resources. Point to outliers all you want, but their coverage of a major war, possibly a defining one, has been terrible. A large part of the reason is that, over the same 20-year period, much of the so-called news business shifted from a reportage model to a reactive model—that is, conversations about what happens in the news versus actual news. This is not only vastly cheaper to produce, it drives traffic on social — the tail now vigorously wagging the dog of journalism. Social media is the driver of news agendas. It is the index by which success is judged, and the wellspring of assignments, since outlets are inclined to chase what is already trending. And, as we have experienced, much of its information is bad.

It is true that in disarray, there are fewer gatekeepers, and new perspectives can burble into mainstream discourse. This platform, for one, exists to empower a multiplicity of voices and may, in the end, revolutionize publishing. Social media in all of its diverse expressions has given rise to armies of so-called citizen journalists. But it turns out that actual journalism is a profession that requires training, investment, and complex structures of support. Nobody would say those citizen journalists (mostly citizen op-ed writers) have led the reportorial charge on Afghanistan. We are still dependent on thinning ranks of establishment reporters to create foundational content, which is then processed endlessly through feeds.

Typically, we use social media to voice outrage and stoke constituencies by marshaling evidence in filtered amen corners. In terms of Afghanistan, is our anger about a destructive policy, or about being forced, however briefly, to look at its consequences? We do so resent being pulled away from our distractions. Polls have long shown Americans’ lack of enthusiasm for the Afghanistan project. It seems we didn’t expect the optics to be so upsetting. Policymakers have a lot to answer for, but inattention belongs to us.

When such awful things happen, we now have expansive channels to express full-throated grief that transcends simply laying flowers at the embassy gate. Social media is excellent for posting a black square and bickering about the moral posturing behind posting a black square. Most effectively, it speeds the dissemination of the most cinematic tragedies, be it the story of George Floyd, or that of Zaki Anwari, the 17-year old Afghan who plunged from a military plane as it left Kabul.

Reacting to these wrenching events on our platforms is now an ingrained part of the human routine, which reached new heights during the isolation of the pandemic. Where else can one reliably go to rail against injustice? This is derided as virtue signaling, but there are worse things than to signal virtue in the face of horror. One of them is saying nothing at all. Since the Arab Spring, social media has provided us with a pain agora, the new church of suffering. At least in that way, it has proven to be the knitter-together of constituencies often advertised, even a cudgel against the powerful. On the other side of the scale, one might put that collective kvetching is not proactive. It typically arrives at a point in the cycle when the actors with real, brutal power have already done their worst.

Somewhere before that happens, actual journalism must find its way, whether or not the important topics it covers are magnets for likes. Reporters are arguably more inclined than typical people to be seduced by incentives to become influential. If they are still employed, they are also very likely to work for organizations that use digital metrics as indices of success. Let us pause here to say that the old adage Numbers Don’t Lie is, in fact, a whopper. Numbers can lie outrageously and quite prolifically, and few if any people running legacy media corporations know what they mean. Nevertheless, human beings are perennially awed by them, nowhere more than in the new information economy (see Justin Bieber above). The many mistakes made by content companies in the digital age hinge on this. The great seduction of new platforms was that they could science troubled industries run by liberal arts types out of big problems, that they could turn a crapshoot (what makes audiences like stories) into something reliable and mathematically girded. Quite obviously that hasn’t happened.

We now know that a hyper-focus on traffic cheapens the value proposition of content and possibly long-term journalistic returns, that pushing engagement, at all costs, is dangerously warping, and that giant audiences are not necessarily meaningful ones. We understand that our evolving information systems are not leading us to greater enlightenment because they weren’t particularly designed for the purpose. The companies that control them are at best conflicted about being seen as super-publishers versus tech companies who happen to be shopping galleries of user-generated content. Without more effective ways of privileging information over incitement, social media is too often a place for gathering wool from an ever-shrinking guild of weavers. The newsletter revolution is exciting, but by their definition, newsletters are a tailored, subscriber’s medium, the diametric counter to the big spray of old mass media.

When you are the portal by which much of humanity views and interprets their world, you have won the world, warts and all. Even the Taliban is on Twitter. Nine years from now, I’m sure I still will be, too. By then, I assume that by then we will have accepted that we rely on social media for far more than its distractions. In the meantime, I intend to use those platforms not merely as a repository for my pithy takes, but to recommend actual books. In the case of Afghanistan, there are many good ones. They may require a bit more patience, but they are a remarkably durable platform, that, more often than not, deepen the perspectives of their users (see below).

As the bad news from Central Asia filtered back to us all last week, there was a lazy tendency to write about the fall of Kabul as a signpost of imperial decline — our Battle of Manzikert. It’s just as easy to see it as a symbol of Western supremacy — the kind of overwhelming power that makes it possible to stay oblivious. That’s a luxury unimaginable to the Afghan people, who find themselves, not for the first time, the unhappy fly on the back of a feckless elephant. In real terms, too few of us paid any price for such a tragedy. Our alluring media didn’t even levy the small tax of making us pay attention. We outsourced suffering while we looked at our phones.

Selected Books About Afghanistan

The Histories: The so-called “graveyard of empires” has a long history of foreign intervention that cannot be understood in Tweets. The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk explores the 19th-century struggles between Russia and Britain that echo tragically today. Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History, by Thomas J. Barfield, is an accessible introduction to the country and its conflicts, and The American War in Afghanistan: a History by Carter Malkasian, is the first comprehensive account of America’s entire involvement.

Journalism: Steve Coll’s Ghost Wars and Directorate S: The CIA and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan explore U.S. covert operations and the limits of American power. The Punishment of Virtue: Inside Afghanistan After the Taliban by Sarah Chayes is a deeply personal look at how U.S. efforts at reform failed. Sebastian Junger’s War experiences the conflict through the eyes of American troops.

The Taliban: Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia by Ahmed Rashid is the definitive work on the Taliban in English. A startlingly direct account from one of the group’s founders, Abdul Salam Zaeef, My Life with the Taliban will not reassure anybody hoping for moderation from the new regime.

The Afghan People: When it comes to the war that has devastated their country, too few Afghan voices have been heard. Khaled Hosseini is the most famous writer of the Afghan diaspora for his bestselling novel The Kite Runner, but his more expansive A Thousand Splendid Suns threads years of tumultuous history through the lives of two extraordinary women. The Favored Daughter, by Fawzia Koofi, a former lawmaker, is a memoir of the struggle for women’s rights in the country, while U.S. journalist Anand Gopal’s No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes delivers just that.

If you would like to help Afghan refugees, NPR has some worthy suggestions here.