Did one day change us forever, or keep us stuck?

Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically. The cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to have new little hopes. It is rather hard work: there is now no smooth road to the future: but we go round, or scramble over the obstacles. We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen.—D.H. Lawrence

The anniversary story is a reflexively deployed gimmick— a ticket, frequently punched, to a place you’ve already been. What if we blew past the expected peg, and considered not just the red letter date, but all the days that followed? This strategy carries some risk when it comes to holding the attention of an exhausted audience. It presumes that September 11th was more than a singularly terrible event we left behind two decades ago, but a place we can’t seem to escape.

Last Saturday’s twentieth anniversary passed with restrained public commemoration, in no small part due to Covid-19. Alongside the ceremonial laying of wreaths flooded more than 50 televised documentaries and specials, each straining to squeeze meaning from calamity. The problem with such quantity is quantity. In the very cluttered and unsettling year of 2021, even thoughtful people are likely to avoid a mountain of content that raises disturbing questions about where we are now.

Twenty years, that handy media milestone, is in broad historical terms, a blink. If you lived through 9/11, you are possibly still processing what it meant. Perhaps that’s why so many recollections of the day open with the weather. At least one set of details that seems incontrovertible. Those who were in New York City linger on what a lovely day it was as if horror only finds us in the gloom. I can attest that it came, low and loud, out of the cobalt blue. Almost everything about 9/11 now belongs to the world, but that specific sky belongs to those who lived under it in ways that the grotesque spectacle that followed —beamed around the world to billions, recapped in so many slick ways—does not. We can agree that there was a gentle breeze off the harbor and a near cloudless vault of heaven above. Which, we now know, was essential to the plan.

It’s an old and cherished fantasy, this belief that we once dwelt in a time before the Fall. Americans, despite long exposure to violence, are peculiarly addicted to a biblical construction, so evident in 9/11 anniversary narratives. Surely, we were innocents once—before Pearl Harbor, before Vietnam, before riots and assassinations, before the hostage crisis, before the towers fell, before school shootings, before Trump, before the capital siege, before whatever outrage awaits. In this telling, trauma changes goodhearted people and sets them on a bleaker path. But bearing evil, a word that got a lot of use in 2001, is part of our ordinary human routine. Killing, on an extravagant scale, predates 9/11, and continues today, mostly in places we tend to ignore.

This is not to suggest that 9/11 wasn’t uniquely devastating, a spike on any graph of atrocities. Nearly 3,000 innocents were murdered, in what we never before that day called the Homeland. The global media then at its zenith made it a crime witnessed by millions (it might be different in the age of social media, which would immediately splinter narratives according to audience bias). As cinematic homicide, it has, thankfully, not been eclipsed. Those who lost loved ones walk among us in grief. The most affecting accounts of 9/11 will always be their stories of irrevocable loss. That is why we repeat them, habitually reaching for that bromide, Never Forget.

There is tension in those words. For whatever edifices to memory we construct, cannot help but forget, not headlines, but fine threads of experience that become harder to grasp with the passage of time. We become reliant on media to distill unreliable reminiscence and feed it back to us. My own recollections are fragments: The sky became a yellowy soup, there was the smell of cinders, and people, covered in toxic dust, streamed up Broadway, walking home to Westchester and beyond. I went to St. Vincent’s Hospital in the Village to report on survivors who never came. Everybody gave blood, but that exercise presumes mass casualties, and there were none. Somebody’s father worked at Cantor-Fitzgerald, and they needed help putting up fliers (there were fliers everywhere). Military convoys rumbled up and down the West Side Highway as the sun, set over the Hudson in a coral blaze. I worked my way to the edge of a toxic mountain of debris, walking into a sepia twilight ringed by checkpoints, and then turned away from it, into a city that was never more beautiful, very intent getting on with things (the World Trade Center was far, geographically and otherwise, from the heart of that New York). It was a restless time, and then, just briefly, a hopeful time. Ordinary people, not able to do much, wanted to do something, like join the military, learn Arabic, or take the foreign service exam. WNYC played a recording of Jerry Orbach singing a song from The Fantasticks: Try to remember, the kind of September/When no one wept, except the willow.

Anybody who lived through those variations on 9/11 will one day be gone. Actual experience, even raw suffering, dries into an actuarial table. We do not experience a vast granite wall of names, however expertly designed, like the sight of a lone man in a kitchen uniform, plummeting from Windows on the World. The unhappy job of survivors is to somehow absorb terror, and keep trudging along. It’s perfectly human to resist this process, to demarcate horrors we have personally lived through as starkly different from all the rest, designating them hinge-points in history. Fear of forgetting fuels a massive engine, working all the time to pull us back into sadness. At some point, this may not be catharsis, but a kind of stubborn refusal. To move forward from 9/11, is, in some way, to give in to an inexorable process of erosion.

Before the poisoned haze cleared, two main strands in 9/11 storytelling were born. There are the accounts of personal accounts of loss and heroism and there is grim accounting, which, in recent years, has shaped itself into an indictment. The latest crop of September 11th stories is a mixture of these. Among them are stories of children, now grown, who lost parents on that day, and stories of other children, also grown, who happened to be in a Florida elementary school library with President Bush when he got the news. There are memory box interviews with scores of eyewitnesses, and a view from inside the White House as the crisis unfolded. Netflix debuted a documentary series, Turning Point: 9/11 and the War on Terror, and a drama, Worth, about the September 11th Victims Compensation Fund. There are curious outliers—the Vice TV documentary about how comedians responded to the tragedy and Come from Away, the Canadian musical about plane passengers stranded in Gander, Newfoundland. If there is a connecting theme in all these stories, it is that that one day changed us forever (a very familiar line). Once upon a time, the skies were blue, and then it rained ash.

It’s now commonplace to view 9/11 as the beginning of a corrosive period when a great power gave itself over to reaction, paranoia, endless wars, and the betrayal of democratic values. History may or may not repeat itself, but this flavor of historical analysis does, and many of our contemporary accounts of the world since 9/11 could have been written by Gibbon (or Tolkien). We have slid smoothly into recounting the event as the moment when Pax Americana ended, and a dark, uncertain age rose.

There is truth in all of it, but, like any history written while it’s still being lived, it is incomplete. We tell these stories from our corner, and so they are also notable for what they don’t say, and who is asked to speak. Once there was a third strand of 9/11 storytelling, broadly covered under the umbrella title Why do They Hate Us? Bush actually plucked a few chords from this old tune in his anniversary remarks. The bygone intellectual right was consumed with militant Islam, and how the West was locked in civilizational combat, while the left connected these conflicts to oil and imperialism. These ideas clashed in interesting ways, but there was broad consensus about winning hearts and minds in the Middle East. Bush took great pains to distinguish between ordinary Muslims and terrorists. Barack Obama went to Cairo to speak to the Muslim world. Twenty years later nobody wants to have these conversations. There is bipartisan exhaustion, a sense that the best scenario is to keep a watchful eye from a great distance. To do this we bolster the surveillance state and strike our enemies before they strike us. We have had not had another 9/11, but thousands more have died in this effort. Americans were once the world’s most dangerous idealists. Perhaps we are now merely dangerous.

In the aftermath, there was much desire to bury the past there was to cling to it. Fast on the heels of public grieving came full-throated calls to get things back to normal and defiantly rebuild, fast (the devastating health consequences to many who worked in the rubble are a consequence). I remember this not as public policy but as a profoundly felt desire, not a divisive one as it is today. There are critiques of the pace, expense, and quality of reconstruction at the World Trade Center, but a gaping and complex wound was cauterized and stitched up, at least in a physical sense. Twice as many people now live in lower Manhattan as did at the time of September 11th.

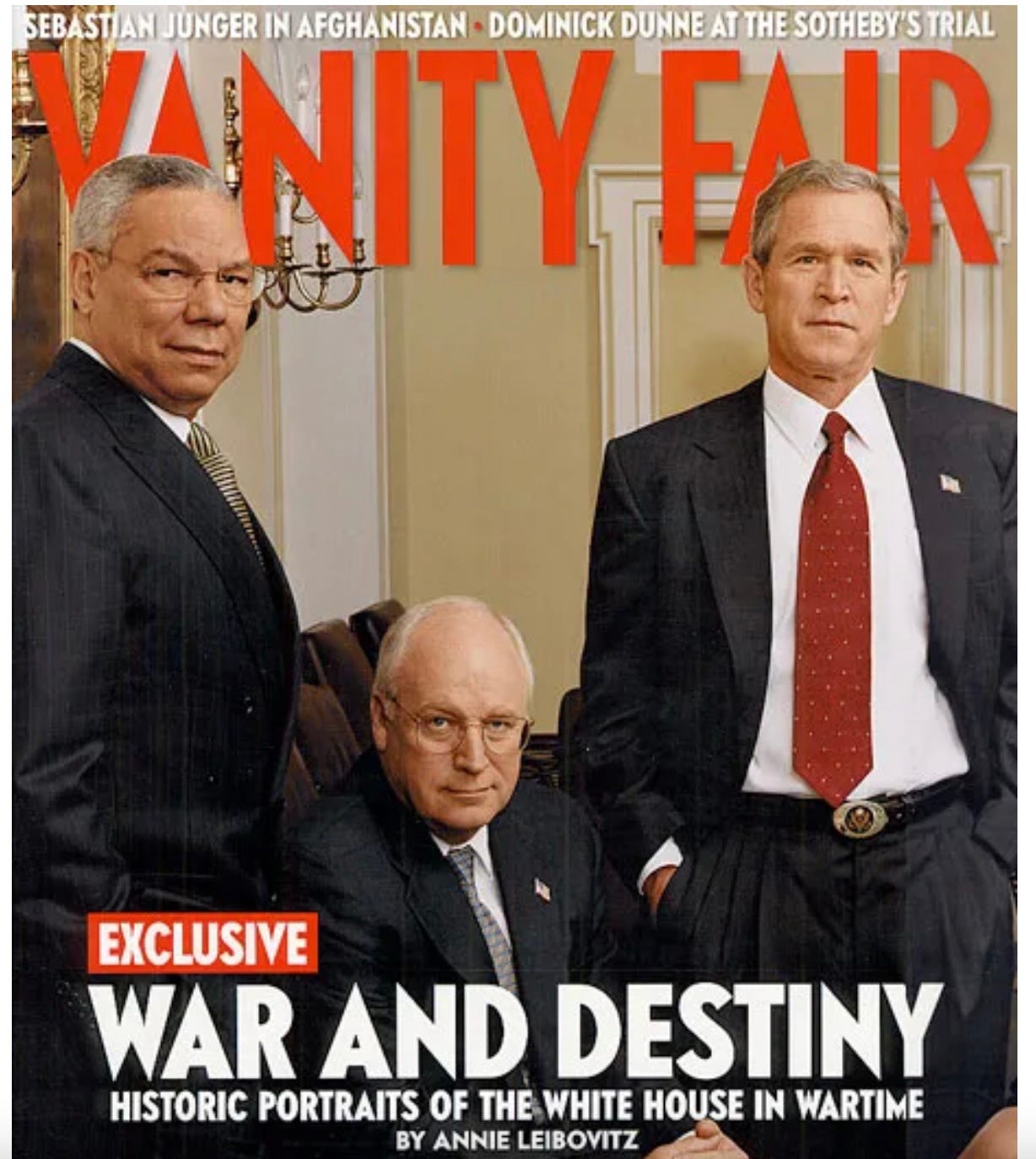

Before the invasion of Iraq, there were many who saw tragedy as the beginning of a new national unity, even revival. Vanity Fair put the Bush White House leadership in February 2002, and many did not find it crazy. Plenty of reasonable types signed up for things now widely condemned as dastardly. Then as now, it wasn’t that there wasn’t a critique, it’s that it seemed almost impossible to resist forces that were pushing us, inexorably, in a terrible direction. Twenty years in the future, the current wisdom will likewise be heavily revised. It clearly takes us more time to glean the significance of a catastrophic moment than it does for a vast media apparatus to leap to conclusions.

Perhaps September 11th did not change us forever. Maybe it did not change us enough, or at all. When we look at 9/11, the era, we tend to narrow the frame to what keeps us mired—in the definition of reactionary politics, in stubborn denial, in humanity’s addiction to revenge. We could easily pick up those threads at an earlier point, and start the doom clock at another moment of martyrdom. We can be certain that the ending is not where we have currently placed it. In many ways, the attacks came in the middle of a very long story about the limits of global power and dangerous entanglements in faraway places. This does not minimize terrible loss or blame the blameless. It is a simple acknowledgment of the continuum of tragedy in a complex world. We stopped being children in it long ago.