Sidney Poitier’s great American life was too big for last week’s tributes

Hollywood obituary leans on hyperbole. When a famous person dies, there’s a rush to ring bells loud enough to rouse distracted audiences, in the hope that a little poetry gins up interest. Pressing the case for a legend is only human, because we mark time in our lives by the people who flit past on our screens. When they depart, something ends for us, too. Tributes to immortals are a protest against mundane mortality for everybody else.

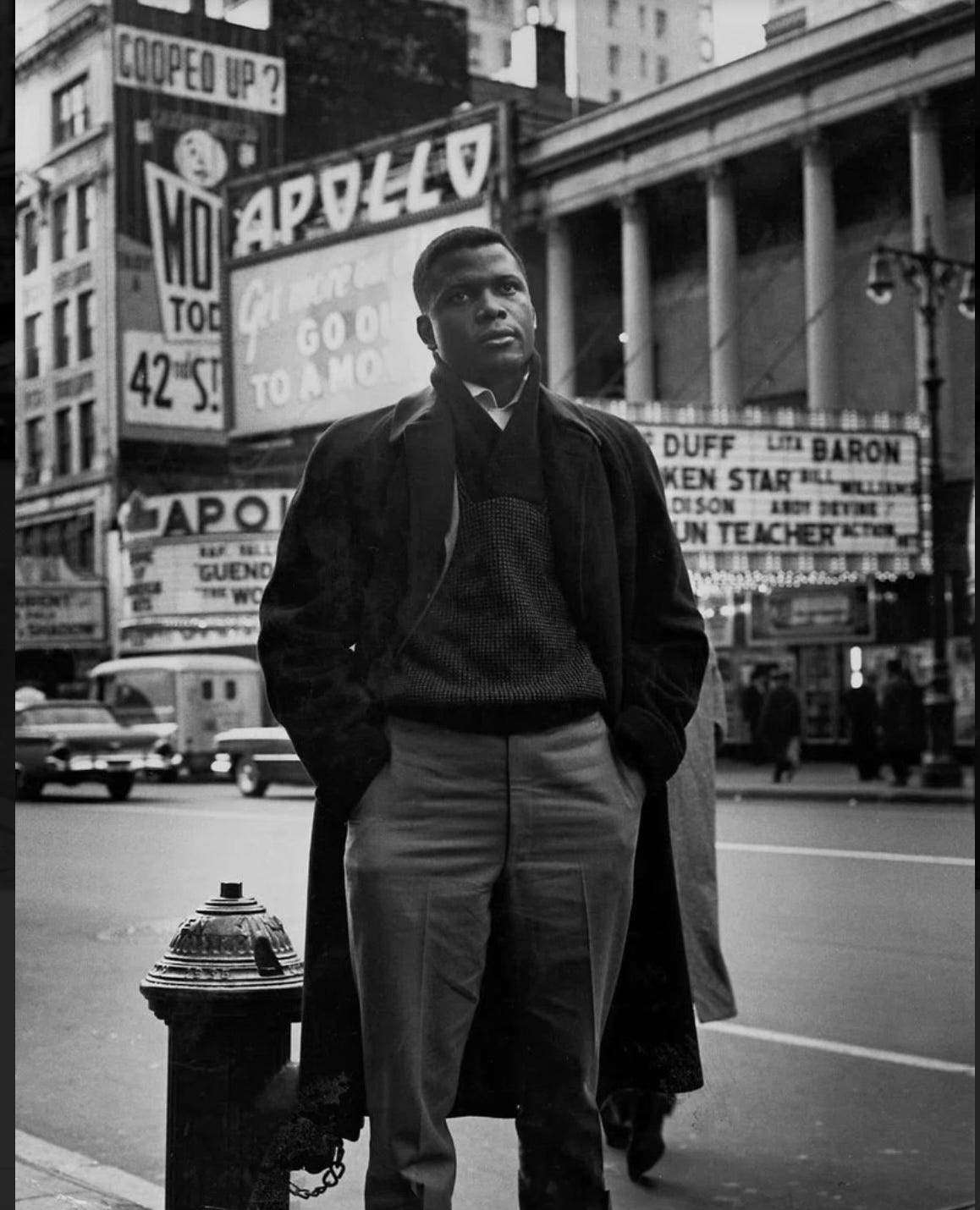

Sidney Poitier, who died at 94 on Jan. 6, was a transcendent figure of the last century, whose impact on Hollywood, race relations, and the very texture of American life were enormous. It would be hard to overstate this, and yet the flurry of quick fire elegies that jammed inboxes last week did not quite soar. The untimely death of a young celebrity, however low rent, galvanizes the public, but Poitier had lived a long, epic life and had been off the main stage for years. Millions of us did not experience him at the peak of fame, so he is lazily shorthanded as a “trailblazer” from an ancient time. Which is a kind of crime.

Of all people, Poitier understood being reduced to a symbol. He became a movie star at a clinch moment, which called on him to be both a synonym for Black dignity and an ambassador to anxious white audiences. These were impossible burdens, and he weathered actual threats on his life and petty criticism as his career progressed and sensibilities changed. The parts he typically played (and selected) were heroic, bourgeois and assimilated, often unmoored from a specific and potentially unsettling Blackness. By the late 1960s, when he was one of Hollywood’s most bankable stars, neatly pressed rectitude clashed with the radical chic of the day.

“It’s a choice, a clear choice,” Poitier said of his career in jittery 1967, when he starred in three hits — Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, and To Sir With Love. ” If the fabric of the society were different, I would scream to high heaven to play villains and to deal with different images of Negro life that would be more dimensional. But I’ll be damned if I do that at this stage of the game.”

At that stage of the game, the notion of choice for any Black actor was novel, and Poitier was the designated hitter for a race. His persona, onscreen and off, was of an elegant gentleman in a Pierre Cardin suit. This was invention, for his own life began in crushing poverty and his climb to prominence was far more remarkable than any fiction he played.

The man who came to Dinner portraying a brilliant doctor who ran a clinic in Africa left school at 12 and broke into acting as a functionally illiterate dishwasher. As an immigrant and a Black man, he was an alien twice over in hostile territory. Poitier styled his journey as a fierce, individualistic drive to Be Somebody, which makes it a quintessential and reassuring American tale, as well as the myth self-appointed radicals love to quarrel with. Like many of his films, it was too good be true, except that it was.

This spectacular climb aligned with history in advantageous ways. Poitier rose to fame with the civil rights movement, in which he was no bystander, and became the first Black leading man to win Oscar (for Lilies of the Field, in 1964) the year after the March on Washington. He was at his most famous when America was riven by strife and assassinations. His Blackness was a matter of simple reality as well as pride. By his own design, he was not an incendiary figure, and he managed, in ways that would find an echo in the 44th President of the United States, to be a standard bearer for an optimistic, post-racial future. Being a steady hand has its price, but it also glides an agenda forward. “History will pinpoint me merely a minor element in an ongoing major event,” he wrote in his 1981 autobiography This Life. “A small, if necessary energy.”

This is a humble brag from someone who knows his place in the narrative. Poitier was born, premature and sickly, in Miami in 1927, where his parents, Reginald and Evelyn, had gone to the city to sell their tomato crop. The Poitiers eked out a living as subsistence farmers on Cat Island, in the Bahamas. Nearly a century later, the fish hook-shaped spit, which is about 48 miles long and no more than five miles wide, remains sparsely populated and mostly undeveloped. The family lived without electricity or running water, and at the complete mercy of the elements. There was often not enough food. In Poitier’s view, a Depression childhood in such a remote place gave him a crucial advantage —racism was not a feature of daily life. After Florida banned the importation of Bahamian tomatoes, the Poitiers relocated to hub island of Nassau, where Reginald became a cabbie. Sidney, the youngest of seven, left grade school to work as a water boy for day laborers.

Destitution defined the family (Evelyn Poitier stitched clothes for her children out of old flour sacks) and Sidney began finding trouble. At 14, he was briefly jailed for stealing corn. “My father said to me I have to get get you out of this country,” Poitier recalled in 1985. “He spent three dollars for my passport. And my mother spent a couple of dollars for a shirt.” Because Poitier had been born in Miami, he was entitled to U.S. citizenship, and was sent by boat to live with his elder brother Cyril in Florida. He did not communicate with his parents for the next eight years, because he had no money to send home with a letter. When he returned for a visit in 1950, he was already acting in films.

Poitier didn’t stay with his brother long. He described Jim Crow as lashing him “like barbed wire,” and was once threatened at gunpoint by the police. New York, with its large West Indian diaspora and more liberal racial attitudes, beckoned, and he headed north. He found menial work, and began a painstaking process of learning to read in order to decipher want ads and navigate Manhattan’s grid, because not all streets were numbered. He lied his way into the service in 1943, when he was 16, and worked in the psychiatric ward of a veteran’s hospital during World War II. After obtaining an early discharge, he returned to an uptown world of back kitchens, rooming houses, and hustle.

The cinematic turn in Poitier’s life came via the employment section of the Amsterdam News, where he spotted a call for actors alongside those for maids, cooks and chauffeurs. He went to an audition for performers at the American Negro Theater, the company that launched the careers of Harry Belafonte, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, and Isabel Sanford, among others. “I had absolutely no interest at all in being an actor,” He said in 2014. “I was a dishwasher…I felt and understood and embraced the fact that I did not have the wherewithal to do much else.”

Poitier lied about his acting experience and flopped his tryout, hobbled by poor reading ability and a heavy Bahamian accent. He was frogmarched out the door, and by coincidence, told to go find work washing dishes. On his way to a downtown employment agency to do just that, he grew rankled by being written off as unworthy of anything better: “I decided then and there I was going to be an actor.” Not because he had theatrical ambitions, but to prove those who had judged him wrong.

Back in kitchens, he lost his accent by imitating the polished Mid-Atlantic accents of radio announcers. Eventually, he returned to ANT, trading admission to its acting academy for work as as the theater’s janitor. A bit part in a 1946 Broadway production of Lysistrata got him noticed, and by the end of the forties, he was working steadily in theater and a leading member of the left-wing Committee for the Negro in the Arts.

From the start, Poitier approached acting with a sense of larger community obligation. He turned down an early movie offer, to play a janitor whose daughter is murdered by mobsters, because he could not accept the character’s passive response to the crime. “I said to myself that’s not the kind of work I want,” he recalled. “My daughter Pam was about to be born, and Beth Israel Hospital told my wife [Juanita Hardy, to whom Poitier was married from 1950 to 1965] that it would be $75 to cover the birth. I didn’t have the money [so] I borrowed against our furniture.”

It set the template for a career. In Poitier’s first movie, Daryl Zanuck’s No Way Out (1950) he played a medical resident treating a racist patient. And of all the roles that followed, he regretted only two: Porgy in Otto Preminger’s 1959 film Porgy and Bess, which he felt pressured into taking by Samuel Goldwyn and columnist Hedda Hopper, and a “Moorish king” in the 1964 Anglo-Yugoslav swashbuckler The Long Ships. Both failed to meet his standard as role models. “I felt very much as if I were representing 15, 18 million people with every move I made,” he wrote.

Instead, he charted a path by rejecting parts at time when Hollywood offered little to Black actors beyond bits as domestics and gigs in song and dance numbers that could be excised when shown in Southern theaters. Poitier was both tone deaf and determined not to fall into stereotypes (his singing in Porgy and Bess and Lilies of the Field was dubbed). To supplement his income and support a growing family, he ran a Harlem restaurant. But there was growing demand for a new kind of performer. Zoltan Korda’s anti-apartheid film Cry the Beloved Country (1951) with Canada Lee, took him to South Africa and exposed him to the horrors of that country’s racial caste system; Richard Brooks’s Blackboard Jungle (1955) opposite Glenn Ford, gave him a scene-stealing part as wayward teen, and playing a stevedore in Martin Ritt’s Edge of City (1957) propelled him to next-level fame.

In the late 1950s, liberal orthodoxy in Hollywood was framed around notions of colorblind brotherhood, and Poitier played his part in a theater of racial rapprochement. In 1958, he starred alongside Tony Curtis in Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones, the story of two shackled convicts forced to work together to escape prison. Curtis insisted his costar share top billing, and Poitier was nominated for an Oscar and won a BAFTA for his performance. In the film’s final scene, he leaps from a freight train because Curtis’s character cannot keep up, sacrificing freedom for interracial friendship. James Baldwin famously spoke of seeing the picture with a predominately white audience, who applauded, and then a Black one, where someone shouted: “Get back on the train, you fool!”

The Defiant Ones cemented Poitier’s onscreen persona as a proud man damming back vast reservoirs of fury, an apt enough metaphor for a people on the move. In 1959, he returned to Broadway to play Walter Lee Younger in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, which showcased his range and, in a 1961 film adaptation, gave multiracial audiences a rare window into aspects of the Black experience. Poitier’s Walter Lee, a thwarted man who dreams of a life bigger than one allotted him as a chauffeur, loses none of its power 60 years later. Whatever critics say about Poitier’s concessions to Hollywood, it is anything but a deracinated characterization.

For America and Poitier, the 1960s marked a hinge point. In private life, he did not shy away from politics, but the times no longer allowed for such divisions. As a New York actor, he had befriended the blacklisted Paul Robeson, who warned him that “being seen with me will ruin your career.” Poitier was an early supporter of Martin Luther King, Jr., and participated in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom alongside Belafonte, Lena Horne, Paul Newman, Charlton Heston, Ruby Dee, Rita Moreno and others. A year later, King was awarded the Nobel Prize, and Poitier took home his Oscar.

Lilies of the Field, in which Poitier plays Homer Smith, a rambler who helps a convent of German-speaking nuns construct a chapel in the Arizona desert, is hardly groundbreaking cinema, but it was a comforting hit as the civil rights cause was met with increasing violence across the South. Poitier took the role because it was not written for a Black actor, and Smith’s race is never mentioned. In 1964, this was progress, and it was rewarded.

As the decade grew more tumultuous, Poitier worked nonstop, on everything from the biblical epic The Greatest Story Ever Told to A Patch of Blue, about the chaste love of a blind white woman (Elizabeth Hartman) for a Black man. In the latter, the two main characters share Hollywood’s first tame interracial kiss. “To think of the American Negro male in social-sexual situations is difficult, you know,” he later said. “The reasons are legion, and too many to go into.”

At the time, Poitier was a divorced father of four daughters, and in a relationship with Diahann Carroll. (He wed Canadian actress Joanna Shimkus, with whom he had two more daughters, in 1976). But onscreen, there were taboos he was unable to surmount, and much of America was getting impatient. “It is a schizophrenic flight from identity and historical fact that makes anybody imagine, even for a moment, that the Negro is best served by being a black version of the man in the gray flannel suit,” wrote Clifford Mason in a 1967 New York Times piece headlined Why does White America Love Sidney Poitier So? Mason derided Poitier’s heroes as “taking on white problems and a white man’s sense of what’s wrong with the world.”

That critique landed in Poitier’s banner year, when To Sir With Love, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and In The Heat of the Night were all released. “I can tell you what I think the flak was about,” he later told the Washington Post. “For a long time, I got all the jobs — one picture after another after another. And the roles I played were very unlike the average Black person in America at the time. The guy always had a suit, a tie, a briefcase! He was a doctor, lawyer, police detective. Middle-class. The characters weren’t reflective of the diversity of Black life. I don’t know that I wouldn’t have had resentments myself, had I been another actor, on the outside looking in.”

There’s truth in that analysis, but it’s only part of the story. America’s confounding conversation about race, both perennial and always in flux, simply moved too fast for Hollywood. By the time Poitier’s 1967 movies were in theaters, their politics seemed naive to sophisticates. They were much more successful with the everyday public. Poitier brought characteristic intensity even to a these-kids-today melodrama like Sir. (In it, he is an establishment figure, ordering long-haired boys to address girls as “Miss,” while lecturing their miniskirted classmates to stop behaving like “sluts.”) All three films were enduringly popular, even beloved.

In contemporary terms, the most “problematic” of the trio is Stanley Kramer’s Dinner, in which Poitier plays the fiancé of white Katharine Houghton, unsettling her liberal parents, played by Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy. The movie, which scored 11 Academy Award nominations and won two statuettes (for lead actress Hepburn and screenwriter William Rose), has not aged well. But context does matter: When Dinner was filmed, laws against interracial marriage were still on the books, and Loving v. Virginia was decided as production wrapped. If nothing else, it is redeemed by a scene in which Poitier’s Dr. John Prentice declares his independence from his father, played by Roy Glenn. “Dad, you’re my father. I’m your son. I love you. I always have and I always will,” he declares. “But you think of yourself as a colored man. I think of myself as a man.”

Then there is Norman Jewison’s Night, which won seven 1968 Oscars, including Best Actor honors for costar Rod Steiger, and Best Picture. Poitier’s Virgil Tibbs, a Philadelphia police detective investigating a murder in the deep South, is an indelible character — a modern man outraged by the backward world he’s been dropped into. The line, “They call me Mister Tibbs,” became a catchphrase and the title of a 1970 sequel. But another moment, the so-called slap heard ‘round the world, remains one of the most discussed scenes in Hollywood history.

A sequence in which Tibbs is struck by a white plantation owner, played by Larry Gates, and retaliates by returning the favor was reportedly written into Poitier’s contract. “I said, ‘If he slaps me, I’m going to slap him back,’” he recalled in 2013. “I knew that I would have been insulting every Black person in the world [if I hadn’t].” Jewison told Poitier that the movie would not shoot in the South, but ultimately the plantation scenes were filmed over three tense days in Dyersburg, Tenn. The actor slept with a gun under his pillow at a Holiday Inn. “Feelings were that high,” Jewison later told the Directors Guild of America. “This was not a period film. It was taking place in the present moment.”

It was also the high water mark in Poitier’s cinematic career. After the 1968 romantic comedy, For the Love of Ivy, with Abbey Lincoln, he struggled to find his footing with critics and audiences. A remake of the British thriller The Lost Man, which costarred his future wife Shimkus, fashioned Poitier into a Black Power militant on the lam, but was unsuccessful. By the early 1970s the Blaxploitation movie craze and a new generation of filmmakers had pushed him from the center of urgent discussions of race in Hollywood.

This allowed for a third act. In 1969, Poitier founded the production company First Artists with Steve McQueen, Barbra Streisand, and Paul Newman. He turned increasingly to directing films, including the 1980 buddy comedy Stir Crazy with Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. His later acting work, which included two more Tibbs movies and a trio of comedies with Bill Cosby, did not approach the success of his mid-1960s run, but he no longer carried the weight of being The One. By his fifties, Poitier was already being treated as a Hollywood elder statesman, the sort of person on whom laurels are heaped and standing ovations are given. In the 1980s, con artist David Hampton famously talked his way into the lives of affluent white New Yorkers by convincing them he was Poitier’s son, because by then Sidney Poitier was code for respectability in every American household — he was the guest everybody would gladly have to dinner.

Later in life, Poitier occasionally returned to performing (notably as Thurgood Marshall in the 1991 telefilm Separate but Equal, and in a supporting part in the 1992 comedy Sneakers). Among those mountains of honors were a Presidential Medal of Freedom and a knighthood. His 2007 book, The Measure of a Man, as much a set of philosophical musings as a memoir, underscored themes of discipline and dignity that girded and constrained his public image. “You don’t have to become something that you’re not to become better than you were,” Poitier wrote. “A person doesn’t have to change who he is to be better.”

About Sidney Poitier, this was not entirely true. A figure defined by restraint must tuck untold volumes away, and to become a great star, Poitier did mold himself into something better — the necessary man of an era. In ways that would defeat most of us, he changed enormously. Somehow, a society changed with him. But what was at his core—a fire that flashed in his eyes even in cardboard parts, that small but necessary energy—was eternal.