There is no Hollywood without yearning.

At this moment— at any moment—a great number of people in American entertainment are unemployed. In this regard, show business was an early forerunner for the contemporary gig economy, in that it has always been characterized by perpetual insecurity, the perennial audition, the idea that the right connection might secure an individual that lucky break, while a single misstep might have an opposite, calamitous effect, consigning the unlucky to what Lily Bart, the (spoiler alert) doomed heroine of Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, called “the rubbish heap.” People who don’t understand Hollywood often misread it as the land of the vapid, which isn’t exactly true. It is a town full of watchful, frightened people, who tiptoe the line between scarcity and abundance every day. To affect a kind of cheerful blandness in such precarious circumstances is a strategy, and not an unwise one.

Given current trends, it is likely that more and more people will live as those in Hollywood have always lived, which is to say, by their wits. We have long ago left that halcyon midcentury period where an educated middle class person might reasonably expect to have a lifetime job with a comfortable pension. The traditional attitude of the rest of the country toward the people of Los Angeles is that they are nuts, but on closer examination it is easy to divine the method in their madness, a pattern which may serve as a guide to harrowing modern life for us all. Examples of Hollywood Crazy are really just the most exaggerated forms of American Crazy, and American Crazy, whatever the fortunes of the U.S.A., has become the affliction of the entire world. Social media, among its many depredations, has turned us even more into a global culture of hustlers, all vying desperately for the attention of strangers, in the vain belief that attention, above all else, will deliver us the status and lifetime security afforded the fortunate few. This seems a poor substitute for an enlightened social democracy, but that is where we are.

What is it about Hollywood Crazy that we must understand? First, that the essential fuel of show business is hunger, and that hunger will drive people to do all sorts of terrible things to themselves and to others. Mine beneath the outrageous celebrity demand, the vitriolic executive tirade, and the grabbiest negotiating tactic, and you will strike a motherlode of need. When I wrote about Scott Rudin, I focused on our unfortunate tendency to view bullying as the problem of problematic individuals, rather than a universal behavior that we collectively incentivize. But abuse of power is not comprehensible without understanding where that power is derived from in the first place. Rudin was powerful because, in a hunger economy, he had the power to feed people what they most desired. No matter how terrible his reputation, he was irresistible to many who yearned to be close to the white hot light of his success, and have a little of it for themselves.

Exhibit A, of course, is Harvey Weinstein, who collaborated with the best talent in Hollywood despite being, quite obviously, Harvey Weinstein. Recently, an appeals court ruled that some of the most well-known and powerful people in the industry, Bradley Cooper, Jennifer Lawrence, Bill Murray, and Julia Roberts among them, are not entitled to further compensation from projects made with the now-defunct Weinstein Company, whose creative assets are currently owned by an outfit called Spyglass Media. This is a blow to talent, and producers, and dealmakers, one that the unkind might call karmic. That isn’t quite fair. In the long history of Hollywood, it has never been common practice to work only with unimpeachably good people, versus machers who could deliver fame, critical acclaim, money, and awards. We are now in a period when many people feel compelled to apologize for past unsavory associations. This isn’t the worst thing to do, but how can one fault Michael Chabon, Judi Dench, Jamie Foxx, and countless nameless others for wanting to work with individuals the world declared to be the very best? Who would not be hungry for that?

For many years, Weinstein delivered like nobody else, and while the depths of his wrongdoing may not have been universally known, it was impossible to have had even a slight acquaintance with the man and not get a whiff of brutishness. The beastliness of Weinstein (and many others) was part of the package, essential to his success. As I’ve written in Entertainment Weekly, his inability to take no for an answer was what earned him a fortune, as well as what made him a criminal. Like the moguls of a bygone era, Weinstein and Rudin understood hunger innately — they were outsiders, clawers and scrappers, and they knew brutality and rejection themselves. When they achieved great success, they grasped the vulnerability of creative people—producers, writers and most especially actors—and the terrifying yearning of most to be part of the show. People who hold the cards in a starved world exploit yearning expertly, but they don’t have to work so very hard, since there are there are legions who will lunge at opportunity. We can bemoan individual transgressions in Hollywood all day long, but it rather misses the point. It has always been a system for users and of the used. In show business and everywhere else, overhauling victimizing machinery takes more than booting a few baddies in charge.

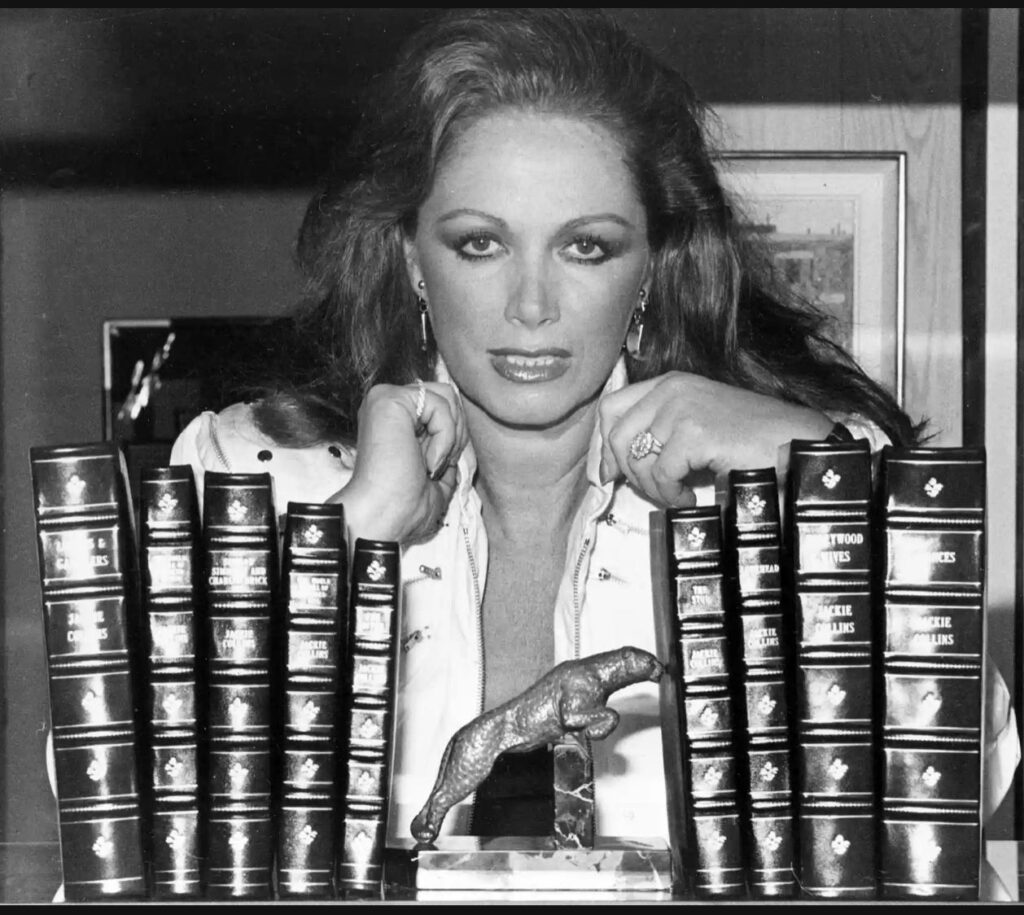

About two weeks before her death from breast cancer, Jackie Collins invited me to her house on North Beverly Drive. I say “house,” when I really mean the closest approximation to the Temple of Dendur I’ve encountered in a private home. The bestselling writer was a bit hollow-cheeked, but in all other ways still in command of an image she had perfected in the 1970s, with a leonine swoop of chestnut hair, a blazer scrunched up at the elbows, and tinted aviator sunglasses. She’d known she was dying for some time, and had carefully scripted an exit, planning an interview with the magazine I worked for, and after that, a trip to the United Kingdom to be on the program Loose Women. While back in her native country she would say goodbye to her younger brother Bill, who was in real estate, and her older sister Joan, who remains resolutely Joan Collins. Loose ends tied up, she would then return to Beverly Hills to expire. It was all very theatrical — almost nobody, including Joan, knew Jackie was sick, and the news of her terminal illness was to be rolled out in this last glorious press campaign. It was also entirely fitting.

Jackie held court in an art deco salon of sorts. It was a residence of cream colored sofas, Patrick Nagel seriographs, marble obelisks, and leaping panther statuary. The pool was designed to look like the one in the David Hockney painting A Bigger Splash. There is no stillness like the stillness of Beverly Hills on a bright, hot day, and even the jacarandas seemed to doze as Jackie talked in her husky-sexy voice about her fictional heroine, the randy Lucky Santangelo, and being at peace with the end of mortal existence. “Like Sinatra sang, I did it my way,” she told our reporter. In this, she numbers among the very few. She flirted madly with me, and showed off her library, filled with bound copies of her manuscripts, each written in long hand. She had no illusions about her writing talent; her brilliance was in understanding human beings. “L.A. is a great town,” she said. “As long as you don’t need anything from anybody.”

She had come to Los Angeles in the 1980s, already a multi-millionaire writer of unapologetically trashy books, and she had lived in comfort, observing Hollywood’s hypocrisies and outrages poolside. She never asked for legitimacy, or indeed for anything from anybody who could withhold it from her. In her way, she had figured out the great secret of lasting show business success — she had created an entire universe, and owned it entirely. Jackie Collins understood the desire that animates Los Angeles, and makes it a place of elusive promise and constant pain. But she refused to audition. It’s a lesson more of us should take to heart. I believe she died at peace, surrounded by those from whom she needed nothing but genuine love. Unlike far too many people, she did not die hungry.